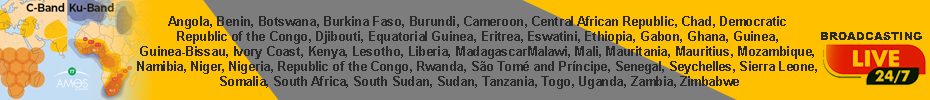

As African leaders convene in Beijing for the latest China-Africa summit, President Xi Jinping may have a noteworthy achievement to highlight: satellite television. Nearly nine years ago, during the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in Johannesburg, Xi pledged to bring digital TV access to over 10,000 remote villages across 23 African countries. With more than 9,600 villages now equipped with satellite infrastructure, this ambitious project is nearing completion. The initiative, driven by China’s aid budget and executed by StarTimes—a private Chinese company active in several African nations—was a strategic gesture of goodwill aimed at enhancing China’s soft power in Africa.

Amidst a challenging economic landscape and shifting Africa strategy, In Olasiti, located about three hours west of Nairobi, local resident Nicholas Nguku gathered his family to watch Kenyan athletes at the Paris Olympics, expressing his joy at finally being able to view such events thanks to StarTimes, which installed satellite dishes four years ago.

StarTimes, which entered the African market in 2008, is now one of the continent’s largest private digital TV providers, boasting over 16 million subscribers. Analysts attribute its success in part to competitive pricing. In Kenya, StarTimes offers monthly digital TV packages ranging from 329 to 1,799 shillings ($2.50 to $14), significantly lower than the 700 to 10,500 shillings charged by MultiChoice’s DStv.

The “10,000 Villages Project” is supported by China’s South-South Assistance Fund, and the satellite dishes prominently display the StarTimes logo along with Kenya’s Ministry of Information and a “China Aid” emblem. This initiative was marketed as a generous gift from China. Dr. Angela Lewis, an expert on StarTimes in Africa, notes that the project was intended to improve China’s image by providing free infrastructure, including satellite dishes, batteries, installation, and a subscription to StarTimes’ content. For many villagers, this was their first experience with reliable satellite TV, revolutionizing their access to global media.

In Ainomoi village, the project’s impact is evident. The local clinic uses a digital TV to entertain patients, while school children enjoy cartoons after class. Eighth-grader Ruth Chelang’at says watching cartoons together is a “very enjoyable and bonding experience.”

Despite the initial enthusiasm, several Kenyan households reported that the free trial period was brief. The financial burden of continuing subscriptions proved significant for many, dampening the initial excitement. Rose Chepkemoi from Chemori village described how the cost eventually became prohibitive, leading her to discontinue the service. Without a subscription, only a few free-to-air channels remain accessible.

Visits to four villages that received StarTimes dishes between 2018 and 2020 revealed that many had stopped using the service after the trial period ended. The chief of Ainomoi village noted that many households opted out of subscriptions due to the expense. StarTimes did not respond to requests for comment regarding the free trials.

The content on StarTimes channels reflects China’s influence, featuring Chinese movies and series, including popular reality shows like “Hello, Mr. Right,” modeled after a Chinese format. Although StarTimes provides some content in local languages and even launched a Swahili channel in 2014, villagers often find the programming outdated and stereotypical.

Football remains the primary draw for many viewers. StarTimes has invested heavily in broadcasting rights for major football leagues and tournaments, including the Africa Cup of Nations (Afcon) and Spain’s La Liga. Despite this, competition is intense, with rivals like MultiChoice’s SuperSport investing heavily in English Premier League rights.

While StarTimes’ efforts to broadcast popular sports are appreciated, some viewers prefer other leagues or local channels. The inclusion of Chinese state broadcaster CGTN in the basic package has not been as well-received, with many preferring local news over Chinese content.

StarTimes has aimed to integrate local perspectives by employing over 95% of its African staff locally. Despite this, the project’s broader impact on China’s image has been modest. Dr. Dani Madrid-Morales suggests that while the initiative was intended to project a positive image of China, its benefits have been limited. The once-celebrated project has become a minor footnote in China’s soft-power efforts.

In conclusion, while China’s satellite TV project has made a notable contribution to media access in Africa, its mixed reception and the financial challenges faced by beneficiaries highlight the complexities of using media as a tool for international influence.