Revitalizing Nigeria’s Cultural Heritage: A New Vision for the National Museum

3 min read

The Nigerian National Museum in Lagos stands as a vital yet overlooked institution, akin to a respected but neglected relative. While it houses invaluable artifacts, it struggles to attract visitors. This challenge stems partly from the colonial legacy of museums, which often feature exoticized objects stripped of their cultural context.

Earlier this year, Olugbile Holloway was appointed to lead the commission overseeing the National Museum, bringing fresh ideas aimed at transforming this perception. He envisions a dynamic approach that involves taking artifacts on the road, reconnecting them with the communities they originated from. “How organically African is this concept of a museum?” he asked, questioning whether the conventional model of a museum is suitable for Nigeria.

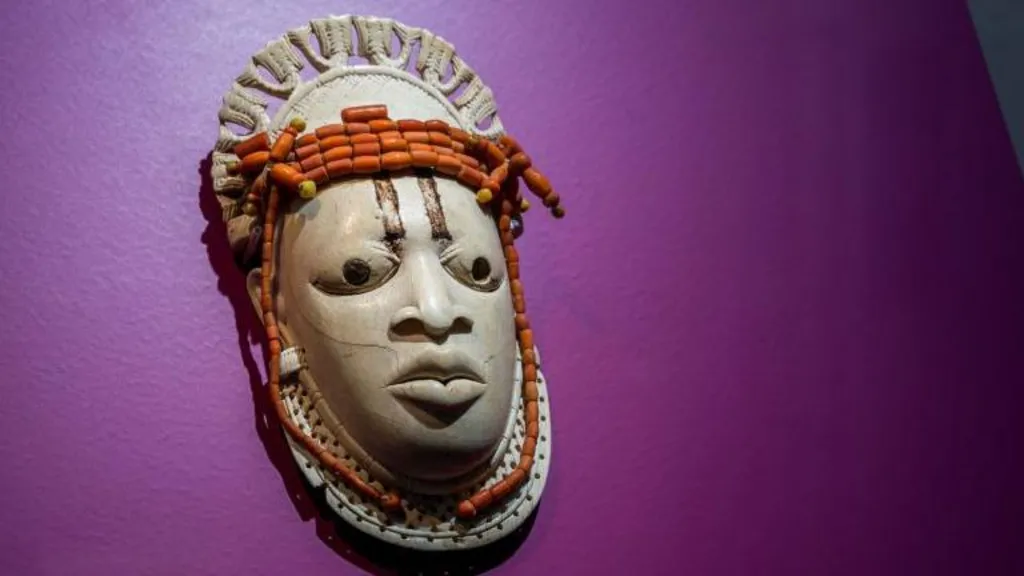

Founded in 1957, just three years before Nigeria gained independence, the museum boasts a diverse collection, including Ife bronze heads, Benin brass plaques, and Ibibio masks. Yet, there’s an irony: Mr. Holloway’s role exists due to the antiquities department established by the colonial government, which sent teams across the country to gather artifacts that could have otherwise been lost to looting or destruction by misguided zealots.

In 1967, an unusual duo, American hitchhiker Charlie Cushman and postgraduate student Herbert “Skip” Cole, undertook a mission for this antiquities department. Their journey through southeastern Nigeria revealed the rich tapestry of local culture, where significant artifacts were often kept in traditional shrines, palaces, or even caves, integral to the community’s spiritual life.

Cushman, now 90, recalled how many villagers were surprisingly willing to sell family heirlooms for a mere couple of dollars—items that could fetch hundreds in Western markets. “To them, these objects were part of ceremonies and cultural expressions, not mere commodities,” he explained.

The duo kept meticulous journals, capturing their experiences and observations of local ceremonies, as well as the resistance they faced from some Christian converts. For instance, they encountered a school headmaster who had burned ancestral figures, viewing them as symbols of paganism. Cole sought to persuade him, arguing for the preservation of these items for future generations. “Could we not send them to the Lagos Museum, where they could be preserved and no longer pose an obstruction to Christianity?” he pleaded. Ultimately, the headmaster agreed, although he could not appreciate their cultural significance.

Reading about these encounters resonates with contemporary experiences, particularly when visiting Western museums that showcase Nigerian artifacts, often taken without consent. Some Nigerian friends visiting London have even refused to photograph themselves with these items, fearing they might be engaging with objects they see as linked to paganism.

The mission of Cushman and Cole stemmed from a larger initiative led by Kenneth C. Murray, a British colonial art teacher, who recognized the need for preserving Nigerian art. Invited by Aina Onabolu, a prominent Yoruba artist, Murray lobbied for better art education and protection for Nigerian artifacts, leading to the establishment of the Nigerian Antiquities Service in 1943 and the creation of several museums across the country.

Cole, who was studying African art at Columbia University, was tasked with gathering artwork from southeastern Nigeria for the new Lagos museum, resulting in the collection of over 400 pieces. Unfortunately, much of this heritage was threatened during the Nigerian Civil War when the Nigerian army repurposed museum artifacts for cooking fuel.

Despite these losses, the legacy of their efforts remains, now in the hands of Mr. Holloway, who is determined to reshape the museum experience in Nigeria. He envisions a more engaging and culturally resonant concept of a museum, one that reflects the lived experiences of Nigerians.

“We have over 50 museums across the country, yet most are not viable because people see them as lifeless,” Holloway pointed out. He believes that to truly honor the artifacts, they should be displayed in ways that reflect their original purpose, as sacred objects rather than mere curiosities.

Through Holloway’s vision, there is hope for a revitalized approach to Nigerian cultural heritage, one that not only preserves history but actively involves communities in its celebration and understanding.