African Nations Pursue Space Sovereignty: The Rise of Satellite Technology

3 min read

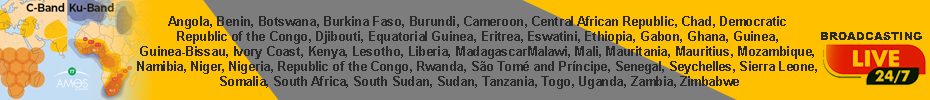

Senegal's first satellite hitched a lift on a SpaceX launcher in August

In a landmark moment for African space exploration, a significant milestone was reached on August 16 when 116 satellites were launched into orbit. Among them was GaindeSAT-1A, the first satellite developed by Senegal. This small CubeSat is designed to enhance Earth observation and telecommunications services, marking a crucial step towards “technological sovereignty,” as described by Senegal’s president.

The decreasing costs associated with satellite launches have opened new doors for African nations. Kwaku Sumah, founder and managing director of Spacehubs Africa, notes that the affordability of space technology is empowering smaller countries to participate in satellite development and deployment. To date, 17 African countries have successfully launched over 60 satellites, with Djibouti and Zimbabwe also celebrating their inaugural satellites within the past year. The coming years are expected to see a surge in satellite launches from the continent.

Despite this progress, Africa still lacks its own space launch facilities. The reliance on foreign technology raises concerns that external powers may use these developing space programs to strengthen geopolitical ties and exert influence. This situation prompts questions about whether more African nations can establish independent paths into space.

“It’s crucial for African countries to have their own satellites,” asserts Sumah. This autonomy allows nations to better control technology and access critical satellite data. Such information is invaluable for monitoring agricultural conditions, responding to extreme weather events, and improving telecommunications in remote regions. However, Jessie Ndaba, co-founder and managing director of Astrofica Technologies, highlights a perception that space exploration is reserved for the elite in Africa. She notes that business in her firm remains slow, underscoring the need for broader engagement with space technology.

The urgent challenges posed by climate change further underscore the necessity of utilizing space technology for monitoring food and natural resources. Ndaba argues against pursuing distant lunar or Martian missions, emphasizing the need to address immediate challenges facing the continent.

Sarah Kimani from the Kenyan Meteorological Department recognizes the significant role satellites play in tracking hazardous weather conditions. She recalls how earth observation data from Eumetsat, a European satellite agency, was instrumental in monitoring a major dust storm in March. The upcoming data from the latest generation of Eumetsat satellites is expected to enhance early warning systems for events like wildfires and lightning strikes.

As climate change intensifies weather-related threats, real-time satellite data—updated as frequently as every five minutes—will be essential for meteorologists. Kimani believes that having more indigenous meteorological satellites would empower African nations to better meet their unique needs, stating, “Only Africa understands her own needs.”

Currently, many African nations with emerging space programs are heavily reliant on foreign technology and expertise. Temidayo Oniosun, managing director of Space in Africa, notes that while some students have been sent abroad to acquire space technology skills, the lack of local facilities hampers their ability to implement what they’ve learned upon returning.

Although Senegal’s new satellite was developed by local technicians, it was made possible through a partnership with a French university, and its launch utilized a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from California. While foreign collaboration has been beneficial, Oniosun expresses concern about the diplomatic implications of such arrangements. The involvement of global powers like Europe, China, and the U.S. in African space initiatives has both advanced technology and created competitive dynamics.

Despite these challenges, Sumah remains optimistic. “We can leverage the interests of these powerful nations to negotiate the best deals for Africa,” he asserts. Julie Klinger from the University of Delaware emphasizes the need for updated global treaties to maintain a peaceful space environment amidst the growing competition.

There are also promising opportunities for African nations. Klinger points out that equatorial space launches could require less fuel, enhancing the potential for African spaceports. For instance, the Luigi Broglio Space Center in Kenya, an older facility, could be revitalized for future launches.

In conclusion, the trajectory for African nations in space is on the rise, with nearly 80 satellites currently in development. Oniosun believes that the future of the African space industry is bright, as nations increasingly assert their presence in the final frontier. With ongoing investment and collaboration, Africa is well on its way to establishing a robust space presence that addresses its unique challenges and opportunities.