Ancient genes show human-Neanderthal mingling 45,000 years ago

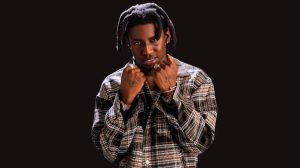

3 min readScientists in Germany have released a depiction of Zlatý kůň woman, the oldest known modern human who settled in Europe after migrating from Africa. Based on DNA studies, Zlatý kůň is thought to have had dark skin, eyes, and hair, reflecting the genetic traits of early humans who made the journey into Europe around 45,000 years ago.

This research, recently published in Science and Nature journals, identifies the group of early humans Zlatý kůň belonged to as distinct from the Neanderthals, with whom they briefly mixed. However, unlike the Neanderthals, whose genes have survived through generations, this group’s progeny did not persist. Dr. Kay Prüfer, a leading researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, emphasized that these early humans represented one of the earliest migrations out of Africa, marking a significant point in human evolutionary history.

Zlatý kůň’s DNA, excavated from a cave in the Czech Republic in 1950, is linked to bones found in Ranis, Germany, more than 20 years ago. This connection helps scientists trace the genetic lineage of early human populations that ventured into Europe. Prüfer explained that all non-African populations carry a small amount of Neanderthal DNA, a result of the genetic mixing that occurred between these groups. This suggests that early humans, after mixing with Neanderthals, formed a shared ancestry that would eventually spread across the globe.

Prüfer’s research also notes that the group from which Zlatý kůň originated likely consisted of a small number of individuals, possibly between 200 and 300 people. Despite this, their descendants did not survive. This early group of humans, although important in the broader picture of human migration, left no detectable trace in the genomes of later non-African populations.

The mystery of why this group did not thrive and leave descendants is a major puzzle for researchers. Prüfer speculates that the group may not have had sufficient contact with Neanderthals, perhaps due to geographical or environmental barriers, or they may have taken different migration routes into Europe, which prevented direct interaction. This lack of interbreeding with Neanderthals might explain why their lineage did not survive.

The findings of Prüfer and his team were corroborated by another research group that used different scientific methods to reach similar conclusions. This independent verification adds weight to the discovery that a small, pioneering group of humans once ventured into Europe but ultimately left no lasting legacy.

Prüfer is optimistic about future research, as ongoing studies continue to shed light on the lives of early humans. Despite these early migrants not leaving a direct genetic trace in modern populations, their story provides a crucial piece in understanding the broader puzzle of human evolution and migration out of Africa.

This research not only provides insights into early human migration but also sheds light on the interactions between different human species, such as the Neanderthals and these early modern humans. The eventual disappearance of this group, despite their close contact with Neanderthals, remains one of the significant mysteries in the study of human evolution. The combination of advanced DNA analysis and archaeological discoveries continues to enrich our understanding of how early humans spread across the globe and interacted with other species.