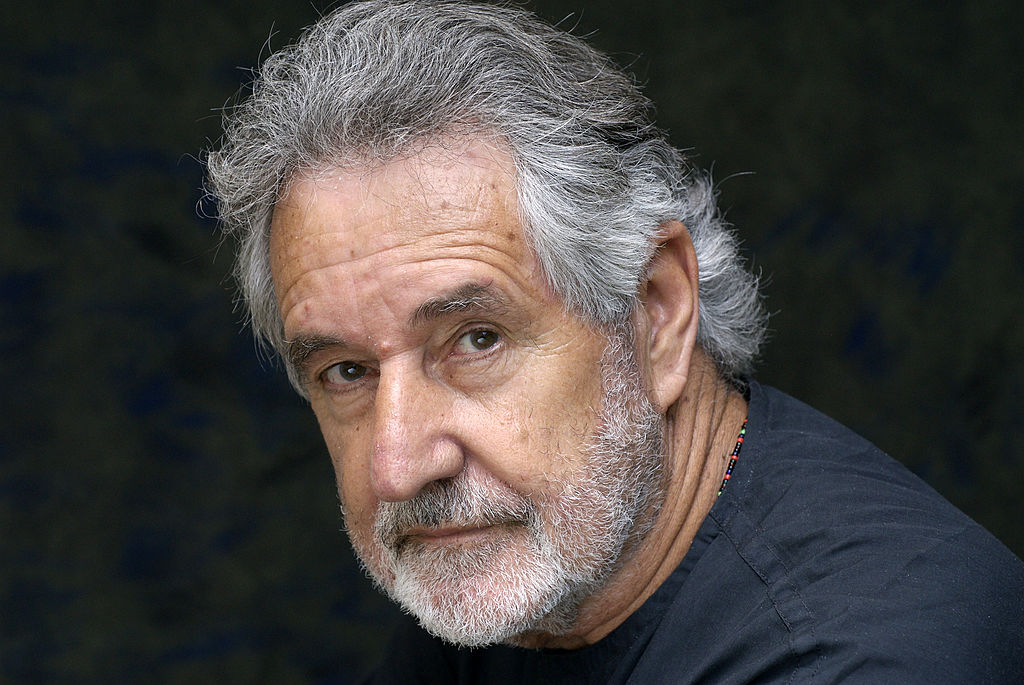

South African anti-apartheid writer Breytenbach dies

3 min read

Breyten Breytenbach was a vocal critic of the apartheid regime

Breyten Breytenbach, the renowned anti-apartheid writer, poet, and activist, has passed away at the age of 85, his family confirmed. He died peacefully in his sleep at his home in Paris, with his wife, Yolande, by his side. Breytenbach, a prominent figure in the fight against South Africa’s oppressive apartheid regime, was remembered as an “immense artist” and a “militant for a better world” by his family.

Breytenbach’s sharp intellect and passionate activism earned him both admiration and respect globally. In the height of apartheid’s brutality, the British satirical show Spitting Image famously referred to him as “the only nice South African” in a song, a testament to his unique role as a dissident voice. His death prompted heartfelt tributes, including one from Jack Lang, former French Minister of Education, who remembered Breytenbach as “a rebel with a tender heart” who fought for human rights throughout his life.

Born on September 16, 1939, in the Western Cape, Breytenbach grew up in a family of five. His early life in South Africa profoundly shaped his later work, which critiqued the brutalities of apartheid. A graduate of the University of Cape Town, he was part of the Sestigers, a group of Afrikaans writers and poets seeking to use their language to both express its beauty and critique the regime. However, as apartheid’s racial policies increasingly sullied the Afrikaans language, Breytenbach rejected the political identity tied to it. In an interview with The New York Times, he famously declared, “I’d never reject Afrikaans as a language, but I reject it as part of the Afrikaner political identity.”

In 1960, Breytenbach left South Africa for Europe, beginning his long period of self-imposed exile. Although living abroad, he remained a vocal critic of apartheid and continued his work as a writer and activist. During his time in Europe, he met his wife, Yolande Ngo Thi Hoang Lien, a Vietnamese woman. Their relationship, an interracial marriage, was illegal under apartheid, which prevented her from accompanying him on a return trip to South Africa.

Breytenbach’s clandestine return to South Africa in 1975 proved costly. He was arrested for attempting to assist resistance movements within the country and was charged with terrorism. He was sentenced to seven years in prison, during which he endured brutal conditions, including two years of solitary confinement. Despite this, Breytenbach continued to write, producing some of his most significant work while behind bars. His experiences during imprisonment became the basis for his renowned novel The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist, which chronicles the psychological toll and physical suffering he endured during his years in detention.

Breytenbach’s release in 1982 came about through international pressure, including the efforts of then-French President François Mitterrand. Shortly after, he became a French citizen. Despite the end of apartheid, Breytenbach remained critical of the new South African government, particularly the African National Congress (ANC), which he accused of becoming a “corrupt organization” after coming to power under Nelson Mandela. His dissatisfaction with the ANC mirrored his broader global activism.

In addition to his literary contributions, Breytenbach was outspoken on other political issues. In 2002, he wrote an open letter to Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, criticizing Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. In the letter, he emphasized the importance of acknowledging the rights of both Israelis and Palestinians to the same land, stating, “A viable state cannot be built on the expulsion of another people who have as much claim to that territory as you have.”

Throughout his career, Breytenbach published over 50 books, including poetry collections, novels, and essays, many of which were translated into multiple languages. He also garnered attention for his surreal paintings, often depicting humans and animals in confined spaces, symbolizing the struggle for freedom and human dignity. In recognition of his cultural contributions, he was made a Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters, one of France’s highest honors.

Breytenbach leaves behind his wife, Yolande, his daughter Daphnée, and two grandsons. His passing marks the end of a life that was dedicated to fighting injustice, whether it was through the pen, his activism, or his art. His legacy, which includes his powerful writings, will continue to inspire future generations in the ongoing struggle for human rights and freedom.