The Muslim group that doesn’t fast or perform daily prayers

6 min readAs dusk settles over Mbacke Kadior, a village in central Senegal, the rhythmic chants of the Muslim worshippers dressed in patchwork garments fill the air.

Gathered in a tight circle outside a mosque, the Baye Fall followers sway and sing at the top of their lungs, their voices rising and falling in unison. The flames of a small fire flicker in the background, casting dancing shadows on their multi-coloured clothes.

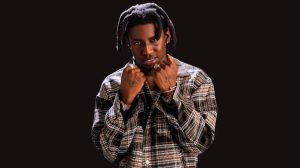

Their dreadlocks swing as they move, and their faces shine with sweat and fervour during this sacred ritual, known as the “saam fall” – both a celebration and an act of devotion.

Participants often appear to be in a trance during the chanting that can last for two hours – and takes place twice a week.

The Baye Fall, a subgroup of Senegal’s large Mouride brotherhood, are unlike any other Muslim group.

They make up a tiny fraction of the 17 million population in Senegal, a mainly Muslim country in West Africa.

But their striking appearance makes them stand out, and their unorthodox practices are believed by some to stray too far from Islamic norms.

For Baye Fall devotees, faith is not expressed through five daily prayers or fasting during the holy month of Ramadan, like most Muslims, but through hard work and community service. In their eyes, heaven is not merely a destination but a reward for those who toil.

They are often misunderstood by other Muslims – and there is also a misconception in the West that some drink alcohol and smoke marijuana, which is not part of their ethos.

“The philosophy of the Baye Fall community is focused on work. It’s a mystical kind of working, where labour itself becomes devotion to God,” Maam Samba, a leader of a Baye Fall group in Mbacke Kadior, tells the BBC.

They feel each task – whether ploughing fields under the relentless sun, building schools, or crafting goods – is imbued with spiritual significance. Work is not merely a duty; it is a meditative act, a form of prayer in motion.

It is here in the village of Mbacke Kadior that the community believes their founder, Ibrahima Fall, first met Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba, who in the 19th Century established the Mouride brotherhood, a branch of Sufi Islam, that plays an influential role in Senegal.

Fall is said to have dedicated himself entirely to Bamba’s service and often neglected his own needs, including eating, fasting, praying and taking care of himself.

His followers recount that over time his clothes became worn and patched, reflecting his selfless devotion. This is how the Baye Fall philosophy and tradition of patchwork clothing originated.

This kind of loyalty to a religious leader is what his followers now practise – a concept known as “ndiguel” – many Baye Fall even include the word in their children’s names.

Fall’s work ethic is also reflected in the heart of Mbacke Kadior at a workshop where collaboration and creativity thrive to create beautiful patchwork clothing.

Women work with quiet focus, dipping plain fabrics into vats of vibrant dyes. With each dip, the cloth absorbs layers of rich, bold colours, gradually transforming into striking textiles.

The men, equally meticulous, take the dyed fabrics and skilfully sew them into garments that are both practical and expressive of the Baye Fall’s distinct identity.

The air buzzes with purpose as the clothing takes shape, a blend of artistry and labour that mirrors their dedication. These finished pieces are then distributed to markets across Senegal, where they sustain livelihoods and share the community’s philosophy far and wide.

“The Baye Fall style is original,” explains Mr Samba, whose late father was a respected Baye Fall sheikh, or marabout as religious leaders are known in Senegal.

“The patchwork clothing symbolises universality – you can be Muslim and still maintain your culture. But not everyone understands this. We say if you don’t accept criticism, you can’t progress.”

While other Muslims are fasting from sunrise to sunset during Ramadan, it is the Baye Fall who dedicate themselves to preparing food for the evening iftar meal when the fast is broken at mosques.

This devotion is not limited to manual tasks.

The Baye Fall have established co-operatives, social businesses, and non-governmental organisations aimed at fostering sustainable development in rural Senegal. For them, work is not just a means of survival but an expression of spirituality.

“We have schools, health centres and social enterprises to create work,” Mr Samba explains. “In our philosophy of life, everything must be done with respect, love, and attention to nature. Ecology is central to our sustainable development model.”

But the group has also received criticism for its practice of begging on the streets.

While asking for money is not against the Baye Fall belief system, it is traditionally done with the intention of taking the contributions back to the leader, who redistributes them for the benefit of the community.

“There are real Baye Fall and what we call ‘Baye Faux’- false Baye Fall,” Cheikh Senne, a former vice-chancellor of Alioune Diop University in the town of Bambey and expert on the Mouride brotherhood, tells the BBC.

In urban centres like the capital, Dakar, the presence of these “Baye Faux” has become pervasive.

“These are people who dress like us and beg in the streets but do not contribute to the community. It’s a serious issue that harms our reputation,” says Mr Senne.

The Baye Fall’s emphasis on hard work and community has resonated beyond Senegal’s borders.

Among their followers is Keaton Sawyer Scanlon, an American who joined a community after a visit in 2019. She has since been given the Senegalese name Fatima Batouly Bah and describes her first encounter with a marabout as a life-changing moment.

“It felt like his body was emitting light,” she tells the BBC. “My heart recognised a truth. This was a profound spiritual awakening for me.”

Ms Bah now lives among the Baye Fall, participating in their projects and embodying their ethos of service. She is part of a small but growing number of international adherents who have embraced the group’s unique path.

The Baye Fall play a vital role in Senegalese society and their involvement in a wide range of agricultural activities is important for the economy.

Each year they swear allegiance to the current Mouride leader, known as the caliph or grand marabout, by donating money, cattle and crops to the brotherhood to show their loyalty.

They are also instrumental in maintaining the Grande Mosque in Senegal’s holy city of Touba, the epicentre of Mouridism – and are in charge of its upkeep.

In Touba they serve as unofficial security guards at the Grande Mosque during big events, like the annual Magal pilgrimage when hundreds of thousands of people come to the city.

For example, they make sure people are dressed modestly, no drugs are sold in the area and that the caliph is not disrespected.

“The Baye Fall have always guaranteed the security of the caliph and the city,” says Mr Senne. “Nobody dares act improperly when a Baye Fall is around.”

Despite disapproval from some, the Baye Fall’s impact on Senegal’s cultural and religious landscape is growing – though they do face challenges in balancing tradition with modernity.

Limited resources hinder their ambitious plans.

Yet their vision remains clear: sustainable development, rooted in faith and service, that could also help some of the huge numbers of unemployed young people in Senegal who despair of finding a livelihood.

Many of the thousands of migrants making dangerous sea crossings to Europe come from Senegal.

“We want to do more,” says Mr Samba. “We want to create more employment – because young people need it here in Senegal.

“We need collaboration with governments and international organisations. This is our hope for the future.”

For them, hard work is the answer to both the country’s economic and spiritual needs.

Source: BBC