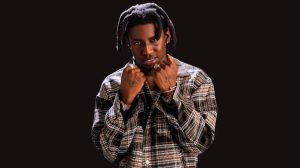

Guled Diriye, a 29-year-old smuggler, collapses into a chair in his dilapidated villa in Mogadishu, weary from his latest venture into the perilous world of alcohol smuggling. His sandals, caked with orange desert dust, tell the story of a grueling journey from the Ethiopian border, fraught with danger and uncertainty. The weight of his experiences, including the tragic loss of a fellow smuggler, lingers in his dark eyes, marked by sleepless nights and tense encounters at armed checkpoints.

“In this country, everyone is searching for a way out,” Diriye reflects, noting that smuggling has become his means of survival amid dire economic conditions. While alcohol is illegal under Somalia’s Sharia law, demand remains high, especially among the youth. Diriye’s journey into this illicit trade began when a neighbor, Abshir, introduced him to alcohol smuggling after Diriye’s livelihood as a minibus driver dwindled due to the rise of rickshaws.

“I started picking up boxes of alcohol at designated drop points in Mogadishu,” Diriye recalls, realizing too late that he had crossed into a dangerous new world. His operations quickly expanded, taking him across the porous Ethiopian border and into Somalia’s rural areas.

Alcohol, primarily sourced from Addis Ababa, is transported through towns like Jigjiga in the Ogaden region, which shares a lengthy border with Somalia. The border town of Galdogob has become a significant hub for this illicit trade, despite growing concerns from local tribal elders about alcohol-related violence. “Alcohol causes many evils,” laments Sheikh Abdalla Mohamed Ali, chair of the local tribal council. “It’s like living next to a factory; it just keeps coming.”

Despite the dangers, smugglers like Diriye find lucrative opportunities. “When I transport food, I make the most money from alcohol,” he explains. Concealment is critical; a loader works to hide the alcohol within the cargo, ensuring they evade detection by various militia checkpoints.

“The average box I move contains 12 bottles, and I transport between 50 to 70 boxes per trip,” Diriye notes. With large portions of south-central Somalia under the control of armed groups, the risks are constant. “You can never travel alone; death is always on our minds,” he admits, though the harsh realities of life compel him to continue.

Navigating the treacherous landscape, smugglers face various clan militias at roadblocks, each with their own demands. Diriye explains the importance of having a diverse team to improve their chances of survival. “If we encounter a militia, it helps if one of us shares their clan,” he says, a strategy borne from necessity.

Tragedy struck for Diriye when a new team member was killed during an ambush. “While I was napping, gunfire erupted. My loader screamed as he ducked for cover. We lost our driver that day,” he recalls, still haunted by the bloodshed. After the chaos subsided, Diriye and his remaining team member laid the body by the roadside, a decision that weighs heavily on him. “I had to wipe the blood off the steering wheel and keep driving; I never imagined I’d witness something so horrific.”

Dahir Barre, another smuggler with a decade of experience, echoes Diriye’s sentiments. At 41, his scarred face reflects years of danger, but his resolve remains steadfast. “We continue despite the risks because the living conditions in Somalia are dire,” he states. Barre transitioned to smuggling after a meager-paying security job proved untenable. “I was earning $100 a month, which now seems absurd.”

Barre notes the escalating dangers in the trade over the years. “Back in 2015, I was getting $150 per trip, but now it’s $350. Al-Shabab had more control then, making encounters riskier.” The Islamist group has a zero-tolerance policy on alcohol, burning vehicles and detaining smugglers, while other armed groups can sometimes be bribed.

The journey from the Ethiopian border to Mogadishu takes about a week, culminating in a carefully coordinated drop-off. “Once we arrive, a group unloads the food products while another takes the alcohol,” Diriye explains. This intricate network ultimately delivers the contraband to local dealers, maintaining a constant supply despite the risks.

Reflecting on his path into smuggling, Diriye remembers how Abshir, his initial contact, quit the trade after losing a family member to banditry. “He turned to religion, and I rarely see him now,” Diriye says.

Yet, he remains undeterred. “Death is predestined; I can’t let fear dictate my life. Sometimes I want to quit, but poverty and temptation are ever-present.” For Diriye and others like him, the perils of smuggling alcohol in Somalia are not merely about survival; they are a stark reminder of the challenges faced in a country torn by conflict and desperation.