‘Give us back our gods’: Inside Nepal’s Museum of Stolen Art

4 min read

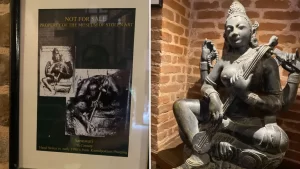

One of the 45 replicas in Rabindra Puri's museum.Sanjaya Dhakal / BBC Nepali

One of the 45 replicas in Rabindra Puri's museum.Sanjaya Dhakal / BBC Nepali

Nestled along a quiet street in Bhaktapur, Nepal, is a unique institution known as the Museum of Reclaimed Art. This unassuming building houses a collection of statues representing Nepal’s revered deities, including a striking sculpture of Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of wisdom. She sits gracefully atop a lotus, adorned with a book, prayer beads, and a veena—an instrument reflecting her artistic essence.

However, these sculptures are not original; they are replicas. The Saraswati statue is one of 45 such replicas crafted by skilled artisans under the direction of Nepalese conservationist Rabindra Puri. This museum is a precursor to a larger facility set to open in Panauti in 2026, designed to draw attention to Nepal’s stolen cultural heritage.

Puri’s initiative is driven by a mission to reclaim numerous artifacts taken from Nepal over the years. Many of these sacred items have found their way into museums, auction houses, and private collections around the globe, particularly in countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. Puri has employed a team of craftsmen to painstakingly recreate these statues, with each replica taking anywhere from three months to a year to complete. Notably, the project has operated without any government funding.

The motivation behind this effort extends beyond mere restoration; it involves securing the return of these stolen treasures in exchange for the replicas. In Nepal, these artifacts are more than just decorative pieces—they are integral to the country’s living cultural practices. Sanjay Adhikari, secretary of the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign, emphasizes that many locals worship these statues daily, often offering flowers and food as acts of devotion.

One poignant story shared by Puri highlights the emotional impact of the theft. A woman who used to worship the Saraswati statue expressed profound sadness upon learning that the original had been stolen, feeling a loss greater than that of a loved one. Such connections underscore the importance of these idols within Nepal’s spiritual landscape.

Unfortunately, the lack of security surrounding many of these statues has made them easy targets for thieves. According to Saubhagya Pradhananga, head of Nepal’s Department of Archaeology, the country has cataloged over 400 missing artifacts, though the actual number is likely much higher. Between the 1960s and 1980s, as Nepal began to open up to the world, a significant number of these items were illicitly taken. Allegations suggest that some high-ranking officials at the time may have facilitated these thefts, enriching themselves in the process.

For decades, the plight of these missing treasures went largely unnoticed by the Nepali public. However, the establishment of the National Heritage Recovery Campaign in 2021 has reignited interest and advocacy for their return. Activists have discovered that many of these stolen idols are housed in Western museums and private collections, prompting them to collaborate with international authorities to press for their return.

The Taleju Necklace, a remarkable artifact from the 17th century, illustrates the challenges faced in these efforts. Stolen from the sacred Temple of Taleju—only open to the public once a year—the necklace was unexpectedly spotted at the Art Institute of Chicago. The discovery shocked many, including Dr. Sweta Gyanu Baniya, a Nepali academic in the U.S., who described her emotional response upon seeing it on display.

Uddhav Karmacharya, the chief priest of the Temple of Taleju, is determined to see the necklace returned, claiming its repatriation would be a pivotal moment in his life. The Art Institute has acknowledged receipt of the necklace as a gift from the Alsdorf Foundation but is currently awaiting further documentation from the Nepali government.

Despite hurdles such as the demand for extensive provenance documentation, some progress has been made. Since 1986, around 200 artifacts have been repatriated to Nepal, with many returns occurring in the last decade. A recent example is the Laxmi Narayan idol, which was returned from the Dallas Museum of Art nearly 40 years after its initial theft. It has since been reinstated in its original temple, where it is once again worshipped daily.

Nevertheless, the atmosphere of concern remains, prompting some communities to install iron cages around their sacred idols for added protection. Puri, however, remains optimistic. He envisions a future where his museum’s shelves are empty of replicas and filled with the original artifacts—calling on institutions worldwide to return these pieces to their rightful home. “Just return our gods!” he urges, affirming that while they can keep the art, the spiritual significance of these items must be honored.