New York first US city to have congestion charge

4 min readNew York City has become the first city in the United States to implement a congestion charge for vehicles entering certain areas of the city. The scheme, which aims to reduce traffic congestion and generate funds for the city’s public transportation network, went into effect at midnight on Sunday. This marks a significant milestone in the city’s efforts to address its longstanding traffic issues and improve the overall quality of life for its residents.

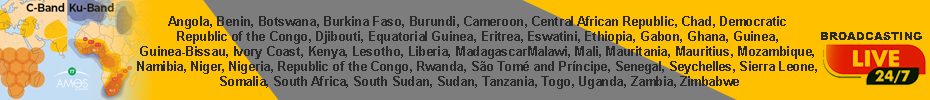

The congestion charge will require car drivers to pay up to $9 per day to enter the designated congestion zone, which covers an area south of Central Park, including popular landmarks like Times Square, the Empire State Building, and Wall Street. The charge varies for different types of vehicles, with small trucks and non-commuter buses paying a higher fee. For example, small trucks and buses will pay $14.40 during peak hours, while larger trucks and tourist buses will be charged $21.60. The congestion zone will be monitored by more than 1,400 cameras, strategically placed across 400 traffic lanes, with over 110 detection points and more than 800 signage installations.

Janno Lieber, CEO of the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA), confirmed that the system began operating as scheduled and emphasized that the charges would be applied using an automated system, which would send tolls to drivers’ E-Z Pass accounts. Lieber expressed confidence that the agreements surrounding the congestion pricing scheme would remain intact even with potential changes in administration, despite opposition from figures like President-elect Donald Trump, who has vowed to end the scheme once in office. The introduction of this congestion charge is seen as a crucial step in addressing New York City’s persistent traffic congestion, which has long been a challenge for its residents.

Governor Kathy Hochul of New York state first proposed the idea of a congestion charge two years ago. However, the plan was delayed and revised after facing opposition from various commuters and businesses concerned about the economic impact. The revised scheme is a version of the one initially proposed by Hochul but was put on hold in June following concerns about its potential unintended consequences for New Yorkers. After careful consideration, the revised version was rolled out in 2025, with a focus on balancing the needs of local residents and commuters with the city’s transportation goals.

Under the new scheme, most drivers will be charged $9 to enter the congestion zone during peak hours, while they will only be required to pay $2.25 during off-peak times. This structure is designed to encourage people to use public transportation during the busiest hours, easing congestion on the streets and improving air quality. Early reports suggest that traffic in areas just outside the congestion zone, such as 60th Street and 2nd Avenue, was flowing smoothly, with few noticeable disruptions.

The congestion charge scheme has encountered significant opposition, especially from New Jersey residents and political figures. Some critics, including New Jersey estate agent Chris Smith, have expressed outrage over the new toll, calling it an unfair burden on drivers. The most prominent opposition has come from Trump, a native New Yorker, who has pledged to eliminate the charge upon taking office. Local Republican leaders, including Congressman Mike Lawler, have joined in calling for Trump to intervene and stop what they describe as an “absurd congestion pricing cash grab.”

New Jersey state officials also attempted to block the scheme just days before its launch, citing concerns over its environmental impact on neighboring areas. However, a judge rejected their efforts to halt the plan, allowing the congestion charge to proceed as scheduled. This development follows a report from INRIX, a traffic data analysis firm, which ranked New York City as the world’s most congested urban area for the second year in a row. According to the report, vehicles in downtown Manhattan were traveling at an average speed of only 11 mph (17 km/h) during peak morning hours, highlighting the urgent need for measures like congestion pricing.

Despite the opposition, there are supporters of the scheme, such as Phil Bauer, a surgeon who lives in Manhattan. Bauer believes that the congestion charge is a step in the right direction to reduce traffic and promote the use of public transportation. “I think the idea would be good to try to minimize the amount of traffic and try to promote people to use public transportation,” he said. For many, the new charge represents a much-needed solution to New York City’s ongoing traffic challenges, with the potential to significantly improve the city’s transportation infrastructure while generating revenue for the MTA.

In conclusion, New York City’s implementation of a congestion charge marks a pioneering moment for the United States as the first city to adopt such a system. While the initiative faces strong opposition from some quarters, its potential to alleviate traffic congestion, improve public transportation, and raise funds for infrastructure improvements is widely recognized. As the city navigates the challenges of this new scheme, it will be interesting to see how the public reacts and whether other U.S. cities follow suit in adopting similar congestion pricing models.