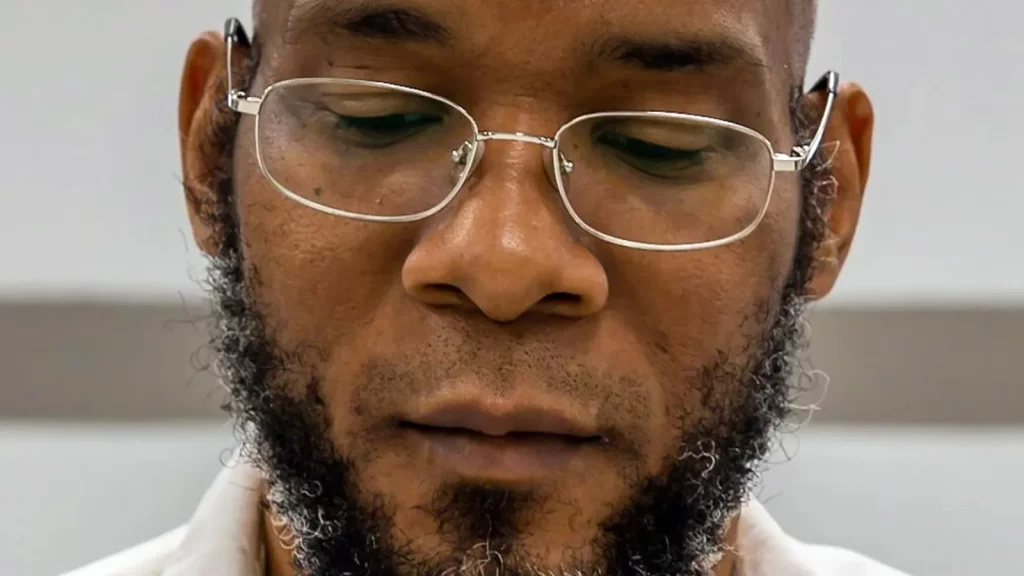

The recent execution of Marcellus Williams in Missouri has reignited intense scrutiny over the Supreme Court’s handling of death penalty cases. Convicted in 2001 for the murder of former journalist Felicia Gayle, Williams was put to death just over an hour after the Court’s conservative justices declined to intervene, despite opposition from three liberal justices who argued that his conviction was unjust.

The execution, which has drawn sharp criticism from civil rights organizations like the NAACP, has highlighted longstanding concerns regarding the fairness of capital punishment. Critics assert that Williams may have been innocent, and they argue that the Supreme Court has failed to adequately protect the rights of those on death row. Data from the Death Penalty Information Center indicates that, in the past two years, the Court has only intervened twice to halt executions out of over two dozen emergency appeals.

Cliff Sloan, a Georgetown Law professor with experience in significant Supreme Court cases, expressed his concerns about the Court’s current approach to capital cases. “In any fair and just society, a freestanding claim of innocence should be recognized as an important constitutional claim,” he stated.

The dynamics within the Supreme Court often see the liberal justices dissenting when capital case petitions arise. When these appeals are reviewed, they frequently split along ideological lines, reinforcing concerns about the consistency and fairness of the death penalty system.

“The Supreme Court has a limited role in death penalty cases,” noted Paul Cassell, a law professor at the University of Utah. He emphasized that state authorities primarily handle these cases with minimal oversight from federal courts.

The death penalty is expected to remain a critical topic for the Court in the coming weeks, with several appeals scheduled for review. Among them is a case involving an Oklahoma woman convicted of killing her husband, who claims that prosecutors degraded her character during the trial by referring to her in derogatory terms.

Another notable case is that of an Alabama man asserting he is intellectually disabled and thus ineligible for execution under existing Supreme Court guidelines.

Upcoming discussions will also include the case of Richard Glossip, an inmate on death row in Oklahoma. Glossip’s conviction stems from a 1997 murder, where the primary witness against him, Justin Sneed, implicated him in exchange for avoiding the death penalty. Glossip seeks to overturn his conviction due to significant prosecutorial errors, including the failure to disclose Sneed’s psychiatric history. Notably, even Oklahoma’s Republican Attorney General has raised concerns about “grave prosecutorial misconduct” in the case.

Williams himself attempted to draw parallels between his situation and Glossip’s, emphasizing that prosecutors had similarly cast doubt on his conviction. St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Wesley Bell has pointed out issues with the handling of evidence, including contamination of the murder weapon.

While Missouri’s state officials stood firmly against Williams’ claims, asserting that the evidence was consistent with the conviction, many advocates argue that the circumstances surrounding his execution raise serious ethical questions about the integrity of the judicial process.

The Supreme Court did not provide detailed reasoning for denying Williams’ request for intervention, though the dissenting justices noted their disagreement. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in particular, has previously voiced her concerns over the death penalty, highlighting the inhumanity of certain execution methods in past dissenting opinions.

Historically, the Supreme Court has played a pivotal role in shaping the landscape of capital punishment in the U.S., having declared in a landmark 1972 decision that many state practices constituted cruel and unusual punishment, violating constitutional protections. However, while this ruling led to a temporary moratorium on the death penalty, it did not abolish it entirely.

The Court’s reluctance to engage in last-minute appeals largely stems from its aim to correct severe misapplications of constitutional law rather than addressing new evidence presented by defendants.

Looking ahead, several critical cases will soon test the boundaries of the Court’s stance on capital punishment. In Alabama, an inmate is contesting his sentence on grounds of intellectual disability, while in Oklahoma, a woman argues that irrelevant details regarding her personal life unduly influenced her conviction.

As these cases unfold, the implications for the future of the death penalty and the Supreme Court’s role in it remain uncertain, but the calls for reform and greater scrutiny are likely to persist.