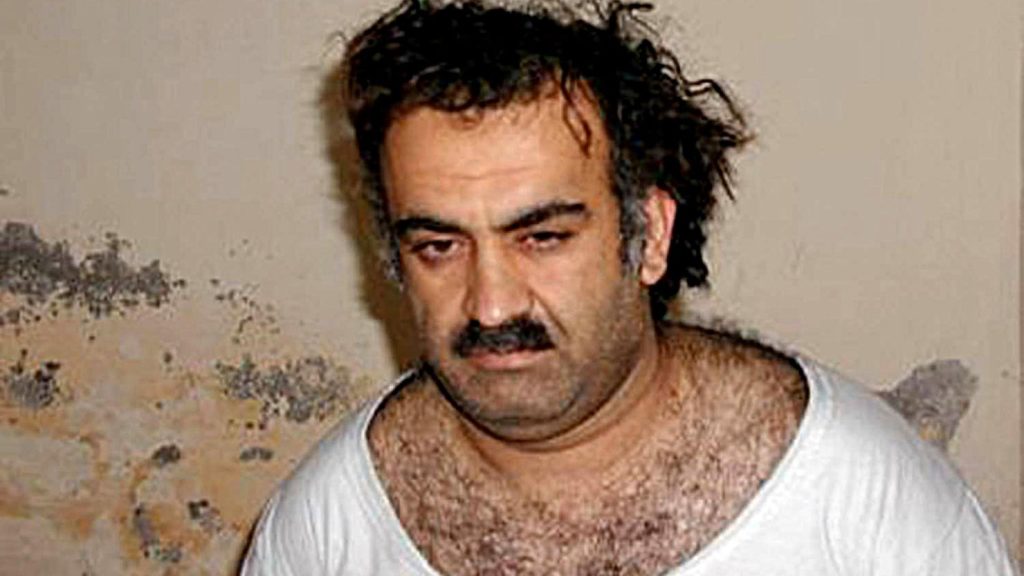

A military judge ruled on Wednesday that plea agreements reached between the U.S. government and the alleged 9/11 conspirators at Guantanamo Bay are “valid and enforceable,” overruling a decision by Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin to revoke the deals. This ruling, made about three months after Austin’s withdrawal of the agreements, means that the accused—Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Walid Bin ‘Attash, and Mustafa Ahmed Adam al Hawsawi—could now be sentenced to life in prison instead of facing the death penalty.

The plea agreements, which were the result of over two years of negotiations, were initially struck in July. The U.S. had hoped to resolve the case with these deals, but shortly after they were made, Austin rescinded them, taking the decision out of the hands of the military commissions’ convening authority, the official responsible for overseeing the courts at Guantanamo Bay.

The defense official told CNN that part of the judge’s ruling was that Austin acted too late in revoking the plea deals. “Not only are the agreements legal and enforceable, but [Austin] was too late in doing that,” the official said. Pentagon spokesman Major General Pat Ryder confirmed that Austin had determined the decision on whether to enter a plea agreement was significant enough to fall under his authority. “We are reviewing the decision and don’t have anything further at this time,” Ryder added.

The plea deals, which had removed the possibility of the death penalty for the three men accused of orchestrating the September 11, 2001 attacks, sparked a public outcry. Critics, including some political figures and groups representing 9/11 victims, argued that the U.S. should pursue the death penalty, and Austin’s move to revoke the deals followed significant pressure. At the time, he stated that the pretrial agreements, which were set to reduce the penalties for the accused, were withdrawn as they were “not in the best interests of justice.”

Following Austin’s decision, defense attorneys for the men argued that the revocation was “corrupt” and violated the rules governing military commissions. According to the military commission regulations, the convening authority may withdraw a plea agreement only before the accused starts performing promises made in the agreement. The defense contended that the accused had already begun to fulfill their obligations, which raised questions about the fairness of the system.

Walter Ruiz, the defense counsel for Mustafa al Hawsawi, called the government’s actions an “unprecedented act” and suggested that it cast doubt on the integrity of the entire military commission process. “It raises very serious questions about continuing to engage in a system that seems so obviously corrupt and rigged,” he said during hearings after Austin’s revocation.

The ruling is a significant development in a case that has been delayed for years, in part due to legal complications surrounding the use of torture by the CIA in the early 2000s. The U.S. government faced difficulties determining whether evidence obtained under torture could be used in court, adding complexity to the prosecution of the accused conspirators.

While the terms of the plea agreements have not been made public, attorneys for the defendants stated in August that part of the deal involved the detainees answering questions from the families of 9/11 victims. Gary Sowards, a defense attorney for Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, noted that some families had already submitted questions to the detainees in good faith, which could have helped offer some closure.

Experts have suggested that a plea deal could have been the best option for avoiding a prolonged trial, especially given the potential legal hurdles surrounding torture-related evidence. Peter Bergen, a terrorism expert, said that reaching some form of resolution through a deal would have been better than continuing with a drawn-out trial process.

Wells Dixon, a senior attorney with the Center for Constitutional Rights who represented another Guantanamo detainee, argued that achieving a death penalty verdict in this case would be difficult, largely due to the government’s reluctance to admit evidence obtained through torture. Dixon suggested that if Austin believed the case could proceed to trial and lead to a death sentence, he was either misinformed or misleading victim families.

As the case continues, the legal and political battles over the treatment of the accused 9/11 conspirators and the possibility of a death penalty remain unresolved. The judge’s decision to uphold the plea deals marks a new chapter in this complex and controversial legal saga.