Why green investments have become the last line of defense for Biden’s climate agenda

12 min read

Wind turbines stand in a corn field in rural Iowa on October 17, 2024. Bill Clark/CQ-Roll Call, Inc./Getty Images

Can the green shoots of clean energy break through the “brown blockade”?

The brown blockade is the phrase I’ve used to describe the hardening tendency of the states most deeply integrated into the existing oil and gas economy, as either major producers or consumers of fossil fuels, to support Republican presidential and congressional candidates who are resolutely opposed to federal action to combat climate change.

Those states moved sharply toward Donald Trump and the GOP in this month’s election. The president-elect won a stunning 26 of the 27 states whose economies are the most reliant on the fossil fuels that produce the carbon emissions driving global climate change. Each of the GOP’s four Senate pickups also came in those higher-carbon states.

In the campaign, Trump promised to take a wrecking ball to virtually all of President Joe Biden’s efforts aimed at reducing carbon emissions and accelerating the shift from fossil fuels to lower-carbon alternatives. The critical role that the states most tightly bound into the existing fossil fuel economy played in both Trump’s victory and the GOP’s success in recapturing the Senate, will only encourage him in that direction.

The only dynamic that might complicate that offensive, even at the margins, may be the green shoots sprouting across large swathes of red America. This torrent of new investments in wind and solar power, the semiconductors used in clean energy, and especially electric vehicles and their batteries – triggered by the Inflation Reduction Act and other economic development bills signed by Biden – has flowed disproportionately into Republican-held states and congressional districts.

Those huge current and planned investments in new manufacturing plants may represent the sole opportunity to preserve any elements of Biden’s blueprint for growing the domestic clean energy industry.

“The beauty of the Inflation Reduction Act is that there is a built-in defense system,” said Lori Lodes, executive director of Climate Power, an environmental advocacy group. “To pull a quote from the ’90s, ‘It’s the economy, stupid.’ There’s hundreds of thousands of new jobs that have been created. Manufacturing is back in the United States. There’s nothing ideological about those jobs. Many of those clean energy workers voted for Trump, I have no doubt.”

The relationship between fossil fuels and red states

As I’ve written before, the broadest measure of states’ integration into the fossil fuel economy is the analysis by the federal Energy Information Administration of how much carbon each state emits in its energy consumption for each dollar of economic output that it produces. The top of that list is centered on two groups of states. One consists of the large producers of fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas (including Wyoming, Louisiana, North Dakota, West Virginia, Alaska, Montana, Oklahoma and Texas); the other big group is states that are large consumers of fossil fuels because they have either robust agricultural sectors (such as Iowa, Nebraska and Kansas) or big manufacturing industries (such as Ohio, Indiana, Michigan and Wisconsin). Whether as consumers or producers, the high-carbon states are predominantly located in the center of the country.

The states that emit the least carbon per dollar of economic output are mostly coastal states that produce little oil, gas or coal and have transitioned more rapidly into the post-industrial economy of services and high-tech jobs, such as Massachusetts, New York, Virginia, Maryland, Washington, Oregon and California (which does produce some natural gas).

Throughout the 21st century, the high-carbon states have become the foundation of the GOP’s geographical strength in both the Senate and the Electoral College. The Republican dominance of those states dramatically solidified in 2024.

After the 2024 election, Republicans now hold 37 of the 40 Senate seats in the 20 states that emit the most carbon per dollar of economic activity, per the Energy Information Administration. That’s up substantially from the GOP’s control of 32 of the 40 seats from the highest-emitting states after Trump’s first election in 2016.

Three of the Senate seats Republicans this year flipped from Democratic control rank in the top 20 highest-emitting states: West Virginia, Montana and Ohio, all of which have trended sharply toward the GOP over roughly the past 15 years. The fourth Democratic-held Senate seat Republicans captured was in the battleground of Pennsylvania, which ranks 27th in emissions per dollar of output, just above the national average.

Across those 27 states with the highest carbon intensity in their economies, Republicans now control 48 of the 54 Senate seats. (The only Democratic senators in those states are two each in New Mexico and Michigan, as well as Tammy Baldwin in Wisconsin and John Fetterman in Pennsylvania.)

The partisan balance is almost inverted in the remaining 23 states with the lowest level of carbon emissions per dollar of output: Democrats hold 41 of those 46 Senate seats, and Republicans just five. The two parties thus present an almost mirror image across this carbon divide: Ninety-one percent of all Republican senators come from the high-carbon states, while 87% of Democratic senators are elected by the lower-carbon states.

The presidential race tells the same story. Among the 27 states with the highest level of carbon emissions per dollar of economic output, Trump lost only New Mexico. That restored the president-elect’s dominance of the high-carbon states to its level in 2016 (when he also won 26 of the 27 highest-emitting states) after Biden held Trump to just 23 of the top 27 states in 2020. The three former “blue wall” Rust Belt states that Trump recaptured in 2024 – Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin – all rank among those higher-emitting states.

As in the Senate, Democrats dominate the lower-emitting states: Kamala Harris won 18 of the 23 on the bottom of the list, including all 11 states with the absolute lowest level of emissions.

The politics of energy isn’t necessarily the decisive factor in determining the partisan tilt of most of these states. The high-carbon states also usually have other characteristics that lean them toward the GOP. Most, for instance, have fewer racial minorities, immigrants and college-educated information-economy workers than the national average and more evangelical Christians and rural residents. The low-carbon states present the opposite picture on all of those dimensions.

But whether or not energy policy is the principal cause of the electoral divergence between high- and low-carbon states, the effect is unmistakable. The low-carbon states tend to elect Democrats who back measures to advance the transition to a low-carbon energy supply and combat climate change. The high-carbon states overwhelmingly vote for Republicans who back expanded domestic production of oil and gas and who resolutely oppose federal action to reduce carbon emissions. That nearly indivisible phalanx of Republicans constitutes the “brown blockade” in Washington.

Campaign contribution trends reinforce this pattern. As the debate over whether to respond to climate change has intensified over the past quarter-century, the oil and gas industry has shifted its giving almost entirely toward Republicans. In 1990, oil and gas interests split their political contributions about 2-to-1 toward the GOP. But in the last few election cycles, the oil industry has directed nearly 9 in 10 of its campaign dollars toward Republicans, according to OpenSecrets, a nonpartisan group that tracks campaign contributions and spending.

Trump has been especially close to midsize oil companies that remain focused almost entirely on drilling for oil and gas, as opposed to the multinational oil giants, such as ExxonMobil or Chevon, that have diversified more into lower-carbon energy sources. Chris Wright, Trump’s nominee for energy secretary, runs a company focused on fracking for natural gas and has flatly declared, “There is no ‘climate crisis,’” and “the only thing resembling a crisis … is the regressive, opportunity-squelching policies justified in the name of climate change.”

These factors virtually ensure Trump will move to undo many Biden policies opposed by the oil and gas industry. Trump, for instance, is likely to quickly begin the process of rescinding regulations the Environmental Protection Agency approved under Biden requiring auto companies and electric utilities to reduce their carbon emissions (by selling more electric vehicles and deploying more clean power, respectively). (Lee Zeldin, Trump’s nominee to run the EPA, has said his priority for “Day 1 and the first 100 days” will be “to roll back regulations.”) And Trump will likely move rapidly to end the Biden administration’s hold on exports of liquified natural gas and to make more public lands, both on- and offshore, available for oil and gas drilling.

What will Trump do to clean energy?

But while Trump is certain to take wide-ranging steps to boost the oil and gas industry, it’s an open question how far he will go to also hobble its competitors in the emerging clean energy space.

Revoking the Biden EPA regulations for clean cars and electricity will hurt alternative energy producers by reducing demand. But, experts agree, the biggest blow Trump could strike against the growing clean energy industries would be to repeal the interconnected tax incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act that promote both the production and consumption of low-carbon alternatives.

As Congress considers the future of those incentives, the growing importance of clean energy industries in Republican-leaning states and congressional districts could complicate the political equation for GOP lawmakers, even those who represent high-carbon states.

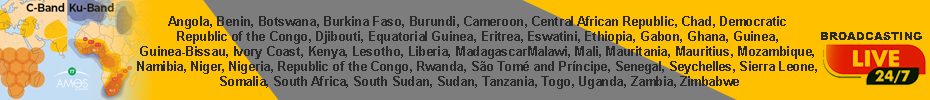

An exclusive recent CNN analysis of data from the nonpartisan Rhodium Group and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for instance, found that nearly four-fifths of the $243 billion in clean energy projects that are either completed or under construction are sited in GOP-held congressional districts. Republican districts are slated to receive an equally large share of another $435 billion in clean energy projects that have been announced but not yet built, the analysis found.

In another recent analysis, Climate Power found Trump won 9 of the 10 states that since passage of the IRA have received the most new investment in manufacturing facilities for clean energy and semiconductors associated with those projects. (New York was the only exception.) Trump also won 7 of the 10 states that have seen the most new jobs created in those sectors since passage of the IRA, the analysis found. Eight of the states that rank in the top 10 for either new clean energy jobs or investment are also among the top 25 states that now emit the most carbon.

If Trump and Congress repeal the IRA tax credits, “I would expect to see announced manufacturing facilities – which are disproportionately [located] in Republican districts –fold up,” said Jason Walsh, executive director of the BlueGreen Alliance, a group that works to unite environmentalists and labor unions. “These are not manufacturers who have economies of scale producing in this country yet. The idea was to give them a glide path with multiyear tax incentives, via the IRA. If that goes away, I think many of those facilities, if not most of them, go away.”

Lodes noted that not only are most of the new clean energy investments flowing into red states, but research shows that the new manufacturing plants are disproportionately sitting in economically distressed exurban and rural communities within those states. “Are they really going to want to turn their backs on communities in their states that have been brought back?” she asked. Moreover, she noted, given that Trump has committed to reducing Americans’ energy costs, will he and GOP legislators “want to take energy off the board, which will just increase people’s cost,” by revoking the IRA subsidies triggering the clean energy manufacturing boom?

Robert McNally, a Republican energy consultant who served as a White House adviser to President George W. Bush, believes the answer to Lodes’ question will be a simple yes. He’s dubious GOP legislators will fight to preserve many of the new IRA provisions beyond those benefiting a few energy options Republicans favor, such as nuclear power and carbon capture. Republicans, he believe, will also likely try to preserve some longer-standing incentives, like federal support for ethanol production.

Beyond that, though, the sweeping new IRA incentives for producers and consumers of electric vehicles and solar and wind “just don’t have deep roots,” among Republicans, McNally said. The idea that auto companies “are building battery factories in, say, Georgia so therefore [Republicans from Georgia] will fight repeal of the IRA incentives – I don’t see any sign of that.”

Certainly Republicans have shown nothing but skepticism about the IRA so far. No Republican in either the House or Senate voted for the law when it passed Congress in 2022. After the GOP recaptured the House in 2023, every Republican representative voted to repeal it – even those whose districts were among the biggest beneficiaries of the new clean energy jobs and investments tied to the law.

Still, environmentalists took heart from a letter 18 Republican House members released in August expressing opposition to repealing the IRA’s incentives for building new manufacturing plants – what they considered to be the first sign that the new jobs and investments might be softening ideological resistance to the law.

Walsh said that in a stand-alone vote on the IRA’s future, enough House Republicans might resist full repeal to protect the law – especially given the GOP’s narrow majority.

“The challenge we’re facing is Trump and the GOP leadership in Congress is not going to present members with a simple up or down vote,” Walsh said. Instead, he predicts, the administration will push to repeal key IRA provisions to partly offset the cost for “the trillions of dollars in tax cuts that is the highest priority for Trump and the GOP to pass. So in that context, which I’m sure is the context we will face, the pressure on Republican lawmakers to redistribute money up to the wealthiest Americans is going to be enormous. And that will make the fight a hell of a lot harder.”

No matter what happens to the IRA, experts agree that EVs and low-carbon power sources such as wind and solar will continue to expand their foothold because of technological advances and economic efficiencies.

“Electric vehicles are not Betamax,” said University of California at Berkeley economist Joseph Shapiro, referring to a 1980s technology for recording television programs that was eclipsed by rival products. “This is not a technology that if it doesn’t get a big (government) push it won’t be adopted.”

Still, Shapiro and others agree that government policy can enormously influence the pace of the transition from fossil fuels. In a recent paper, he and several colleagues calculated that repealing the IRA’s $7,500 tax credit for purchasing a new electric vehicle, as Trump has pledged to do, would reduce the sales of new EVs by 27%. Domestically assembled EVs would suffer an even greater 37% decline, they forecast, because of the law’s provisions benefiting vehicles built in the US.

That’s only one example of how the energy decisions made over the next four years could reverberate for decades. The US reliance on the fossil fuels driving climate change has been declining for years, but only at a modest pace. In 2000, fossil fuels provided 88% of the nation’s energy, according to the Energy Information Administration; in 2023, the latest year for which figures are available, that number was 82.5%.

Biden’s agendawould unquestionably accelerate that change: The Rhodium Group has projected that if current policies remain in place, carbon-free sources within the next decade would provide three-fourths of the nation’s electricity, while electric vehicles would comprise two-thirds to three-fourths of new car sales. In all, the group forecasts that under Biden’s policies, fossil fuels over the next decade would fall to anywhere from 75% to as little as 58% of the nation’s energy mix, according to Ben King, an associate director of Rhodium’s climate and energy practice. That’s a much faster pace of decline than in the past quarter-century.

Even in that world, King notes, oil and gas producers are hardly facing an existential threat to their business in any medium-term time frame. “It is a more gradual energy transition than people initially think,” King said.

Yet interrupting that transition by repealing the federal policies benefiting clean energy remains a dangerous gamble. The result could be a vicious downward cycle: less investment in lower-carbon energy alternatives, which means less production, which yields fewer gains from advances in technology and manufacturing efficiency, which means less adoption, which translates into further reductions in clean energy investment and more years with fossil fuels entrenched as the nation’s predominant energy source.

All of that, in turn, would ensure years of greater carbon emissions – with ominous implications for extreme weather and other manifestations of climate change.

“If the world adopts EVs in 2060 rather than 2020, it makes a giant difference for the planet because there is 40 years of burning gasoline rather than using a cleaner grid,” Shapiro said. “So the pace of adoption matters even if we end up at the same place in the end.”

The brown blockade in Washington can’t entirely stop the shift from fossil fuels to a low-carbon energy future – but, as the first months of Trump’s second term may quickly demonstrate, it can significantly slow the change, and raise the cost of delay.